DURHAM, N.C. — A report released by the Southern Coalition for Social Justice notes that nearly 70,000 North Carolinians who are completing post-release supervision and felony probation were denied the right to vote in 2017. The report, “The Freedom to Vote: Felony Disenfranchisement in North Carolina,” analyzes available data from the North Carolina Administrative Office of the Courts and offers insights about the origins and effects of the state’s policy of disqualifying citizens from voting after a felony conviction, even following incarceration.

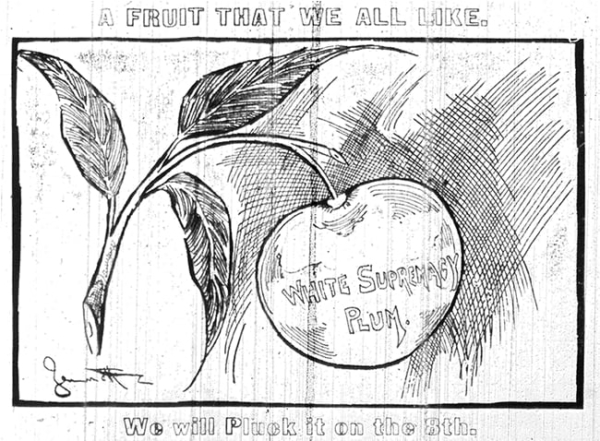

“The impact of this law may be surprising to some, but North Carolina’s approach is not new in the South. It is linked to intentional historic efforts to use state power to marginalize people of color in the post-Reconstruction South,” said Kareem Crayton, J.D., Ph.D., Executive Director of the Southern Coalition for Social Justice. Crayton’s own scholarly research centers on the intersection of law, politics, and race. “Supporters of a whites-only political system crafted laws to criminalize even rudimentary activity by black citizens to undercut the effect of the Reconstruction Amendments to the Constitution. And our federal government either ignored or tacitly supported these efforts. One can draw a steady line between that sad era and the present impact of such discriminatory laws.”

The report illustrates the geographic impact of voter disenfranchisement and explains the confusing system that citizens with a felony record face in order to qualify for the ballot.

“We found a number of problems that demonstrate how people could be easily confused about whether or not they are eligible to vote,” said Kristen Powers, Advocacy Coordinator at the Southern Coalition for Social Justice and author of the report. “Probation offices throughout the state are inconsistently educating people on post-release supervision and probation about their voting rights.”

North Carolina is one of eighteen states that bars people from voting until they complete probation or post-release supervision following a felony conviction. People with misdemeanor convictions do not lose their right to vote. As a step toward an improved system, the report recommends eliminating the confusion by limiting disqualification period to the period of incarceration.

“Creating a bright line focused on incarceration would add clarity to who is eligible to vote,” said Advocacy Coordinator Kristen Powers. “Not only would the change help voters who want to participate in our democracy, but it would also simplify the work of election administrators, probation officers, and district attorneys. We see other states moving in this direction already. Restoring someone’s right to vote when they leave prison is a simple policy change that helps address a very complex problem.”

To view the report, visit southerncoalition.org/resources/the-freedom-to-vote/