REFRAMING PUBLIC SAFETY

Abolish the Death Penalty in North Carolina

The Problem

North Carolina has the fifth-largest death row in the United States. The history of the death penalty in North Carolina is deeply connected with the South’s history of racial oppression. From 1910 until the 1970s, 80% of people executed by the state of North Carolina were Black. Over 60% of the 136 people currently on death row are people of color.

Numerous studies have shown that the death penalty is riddled with error. A landmark study in 2000 examined every capital conviction and appeal nationwide between 1973 and 1995 (nearly 5,500 judicial decisions). Nationally, during that 23-year study period, “courts found serious, reversible error in nearly 7 out of every 10 of the capital cases.” (The majority of people on North Carolina’s death row were sentenced in the 1990s.) In North Carolina, 43 people have been executed since 1976, while 12 people have been fully exonerated. Of the 12 innocent people removed from North Carolina’s death row, 11 are people of color. Those 12 people served a combined 165 years for crimes they did not commit.

.jpg)

Jonathan Hoffman was sentenced to death by an all-white jury, in a case prosecuted by an elected prosecutor who often wore a noose-shaped lapel pin. The elected prosecutor and his assistant were later criminally and civilly investigated for not revealing the various deals promised to a key prosecution witness (including money, immunity, and a reduced sentence for the witness). Mr. Hoffman was granted a new trial once the prosecution’s dealmaking was exposed. After the witness fully recanted his earlier testimony, the charges against Mr. Hoffman were dropped.

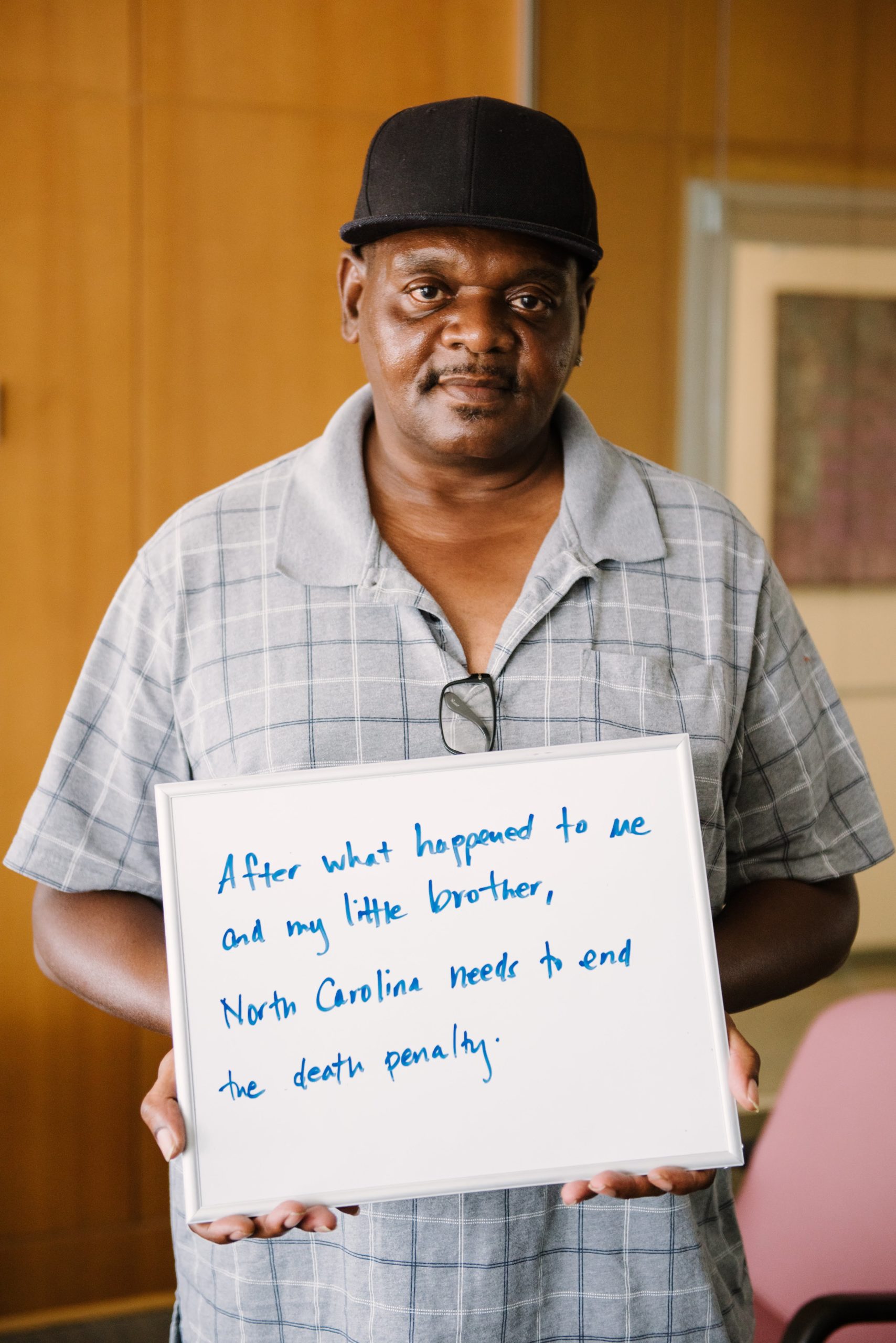

Henry McCollum, whom the late U.S. Supreme Court Justice Antonin Scalia once argued was the perfect example of someone deserving to be executed by the state, spent 30 years on death row before receiving a pardon of innocence from former North Carolina Governor Pat McCrory. (After Mr. McCollum and his brother were cleared of murder and filed a civil lawsuit against those involved in their wrongful arrest and conviction, they were awarded $75 million by a federal jury.

The More You Know

The death penalty does not offer any public safety benefits compared with other sentences. As the U.S. Department of Justice conceded in 2016, “[t]here is no proof that the death penalty deters criminals.”

It is also far more expensive than other types of prosecutions. The last comprehensive study of the economic costs of North Carolina’s death penalty found that the state would have saved almost $11 million per year on criminal justice activities (including the costs of incarceration) if the death penalty had been abolished.

The methods used by state officials to kill people are inhumane. On September 26, 2024, Alabama executed Alan Miller by using nitrogen gas. Media reports described Mr. Miller “shaking and gasping for several minutes before dying on the gurney.” A decade earlier, Oklahoma sought to execute Clayton Lockett by lethal injection. According to witnesses, he moaned and writhed on the gurney for 43 minutes before dying of a heart attack.

Resources

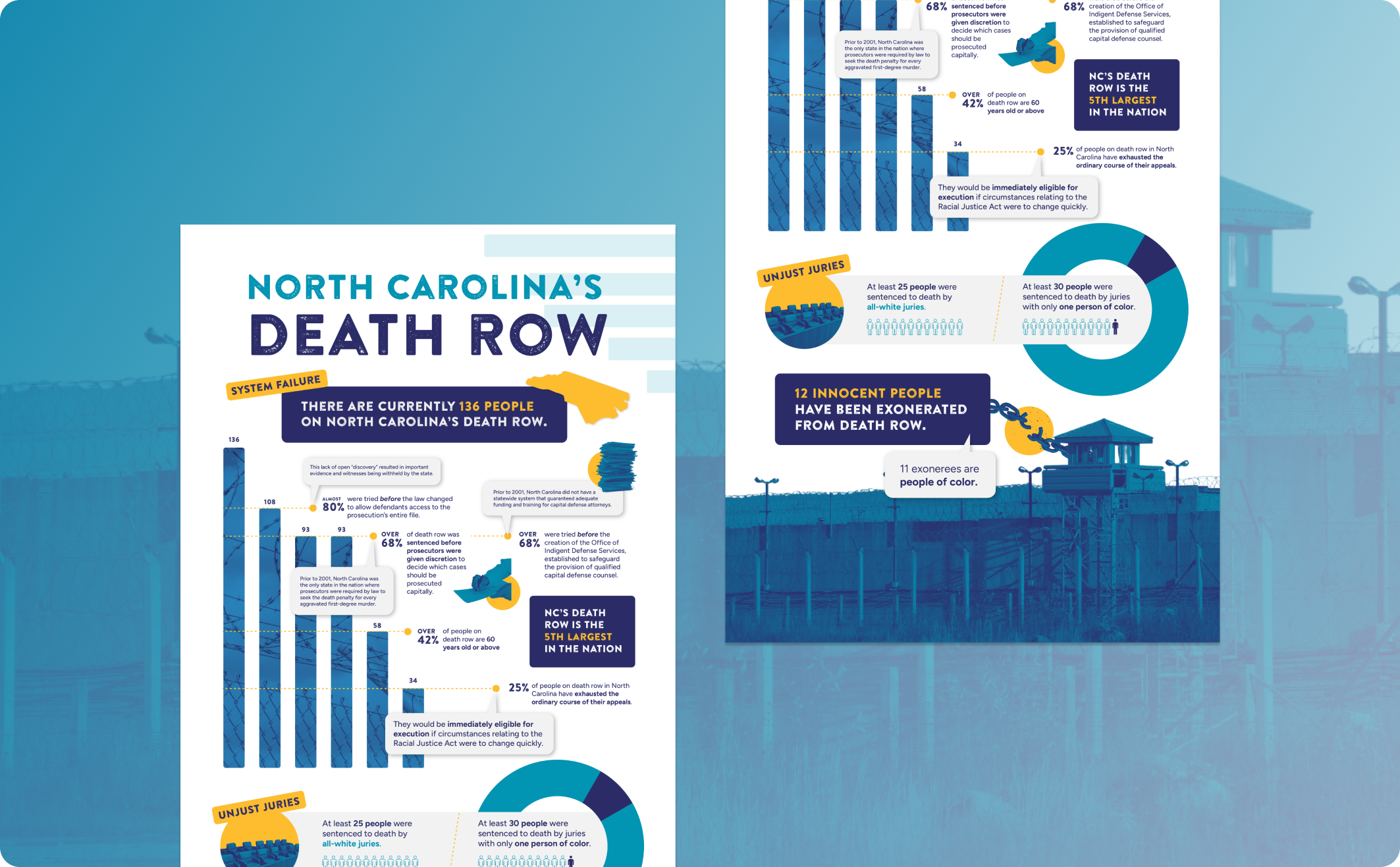

North Carolina's Death Row Infographic

This infographic explains the myriad ways in which NC’s death penalty is a failed public policy that is riddled with error and inequity.

The Case for Commuting NC's Death Row

This booklet lays out a compelling case for commuting NC’s entire death row because it threatens the lives of innocent people, those with severe mental health concerns, and other vulnerable groups, and is infected with racism.

NC Coalition for Alternatives to the Death Penalty

NCCADP is leading a statewide commutations campaign and asking Gov. Cooper to commute all of NC’s death sentences to prison terms.

Jurisdictional Inequity

In North Carolina, as is the case in other states, the death penalty is prosecuted in a small number of jurisdictions. Only 12 counties — out of 100 — account for the majority of the state’s current sentences.

Outdated Policies

68% of people were sentenced to death before the creation of the statewide indigent defense service, which now guarantees adequate funding and training for qualified capital defense counsel in all death penalty cases.

System Failure

68% of people on NC’s death row were sentenced to death before the 2001 repeal of the state’s unique law requiring prosecutors to seek death for every aggravated first degree murder. (That law, the only one like it in the nation, resulted in dozens of capital trials each year and some of the highest death-sentencing rates in the nation.)

Access Denied

79% of people were sentenced to death before death penalty defendants were permitted full access to the prosecution’s files in their cases.

The risk of executions is real and present.

Due to ongoing litigation over the method of execution, as well as North Carolina’s Racial Justice Act, there has not been an execution in the state since 2006. Absent the exercise of gubernatorial clemency or a legislative change, however, it is very likely that executions could move forward quickly once the North Carolina Supreme Court weighs in on State v. Bacote, a case filed under North Carolina’s Racial Justice Act.

The Solutions

North Carolina should join the 23 other states, as well as the District of Columbia, and abolish the death penalty. Since NC’s last execution, the death penalty has been abolished either legislatively or through the courts in 11 states: New Jersey (2007), New York (2007), New Mexico (2009), Illinois (2011), Connecticut (2012), Maryland (2013), Delaware (2016), Washington (2018), New Hampshire (2019), Colorado (2020), and Virginia (2021).

Alternatively, North Carolina’s governor should commute all of the active death sentences in North Carolina. Since the reinstitution of the death penalty in 1976, there have been seven instances where governors have used their commutation power to commute every existing death sentence in their respective state: Gov. Kate Brown in Oregon (2022); Gov. Jared Polis in Colorado (2020); Gov. Martin O’Malley in Maryland (2015); Gov. Pat Quinn in Illinois (2011); Gov. Jon Corzine in New Jersey (2007); Gov. George Ryan in Illinois (2003); and Gov. Toney Anaya in New Mexico (1986). Under the N.C. Constitution, the governor has unfettered power of executive clemency, which includes the power to commute a state death sentence into a life sentence of imprisonment.

The governor could also impose a hold on all executions (i.e., moratorium). Six of the 27 states that still have the death penalty have governor-imposed holds on carrying out executions: Oregon (since 2011), California (2019), Ohio (2020), Pennsylvania (2023), Arizona (2023), and Tennessee (2023).

- For example, in 2023, Governor Josh Shapiro, also a former state attorney general, announced he would not sign any execution warrants and called for abolishing the death penalty in Pennsylvania. That same year, two former governors of Alabama said they regretted not confronting the problems with the death penalty during their respectives tenures: “We both presided over executions while in office, but if we had known then what we know now about prosecutorial misconduct, we would have exercised our constitutional authority to commute death sentences to life.”

Elected Attorneys General have significant discretion when litigating capital cases on appeal or in post-conviction. For example, in 2012, the legislature added language to the post-conviction statute that made clear that prosecutors could agree to granting relief sought by someone challenging the constitutionality of their conviction or sentence. Thus, prosecutors–whether through the Attorney General’s Office or District Attorney’s Office–are empowered to consent to the modification of a person’s death sentence based on a sufficient showing of error or mistake.

Elected District Attorneys can use their experience and positions of power to work towards the elimination of the death penalty. They can exercise their discretion to not seek the death penalty. As noted above, in 2001, the General Assembly modified the death penalty statute by giving prosecutors the discretion to decline to seek the death penalty even when there was evidence of at least one aggravating circumstance. Since change in the law, death penalty prosecutions and sentences have plummeted dramatically. In the last 10 years, for example, there have been only nine new death sentences handed down across the entire state. This prudent and careful use of discretion is in keeping with the powers afforded elected prosecutors under North Carolina law. As the North Carolina Court of Appeals has explained, prosecutorial discretion is necessary to weigh “such factors as the likelihood of successful prosecution, the social value of obtaining a conviction as against the time and expense to the state, and the prosecutor’s own sense of justice in the particular case.” State v. Rogers, 68 N.C. App. 358, 368 (1984). Thus, pursuing restorative justice over vengeance, as well as diligently and humbly reexamining existing capital convictions and sentences (either through prosecutor-led conviction integrity review units, which presently do not exist anywhere in the state, or working with, and not against, innocence projects or commissions), would be in keeping with exercising prosecutorial discretion.

Elected District Attorneys can push for legislative changes concerning the death penalty, whether full elimination or reforms that would significantly narrow the types of cases that would be eligible for capital punishment. For example, in February 2022, scores of elected prosecutors representing communities across every region of the nation, from rural communities to large cities, both Republicans and Democrats, publicly urged all stakeholders “to work together toward systemic changes that will bring about the elimination of the death penalty nationwide.”