The police say the youth shot himself with a hidden gun. But to many residents of this city, which is 40 percent black, the incident fit a pattern of abuse and bias against minorities that includes frequent searches of cars and use of excessive force. In one case, a black female Navy veteran said she was beaten by an officer after telling a friend she was visiting that the friend did not have to let the police search her home.

Yet if it sounds as if Durham might have become a harbinger of Ferguson, Mo. — where the fatal shooting of an unarmed black teenager by a white police officer led to weeks of protests this summer — things took a very different turn. Rather than relying on demonstrations to force change, a coalition of ministers, lawyers and community and political activists turned instead to numbers. They used an analysis of state data from 2002 to 2013 that showed that the Durham police searched black male motorists at more than twice the rate of white males during stops. Drugs and other illicit materials were found no more often on blacks.

After having initially rejected protesters’ demands, the city abruptly changed course and agreed to require the police, beginning last month, to obtain written consent to search vehicles in cases where they do not have probable cause. The consent forms, in English and Spanish, tell drivers they do not have to allow the searches.

“Without the data, nothing would have happened,” said Steve Schewel, a Durham City Council member who had pushed for the change.

The protests in Ferguson — which may return in force when a grand jury decides whether to indict the police officer — may yet help rewrite the relationship between the police and communities there and in other cities. But what quietly played out in Durham may provide another model for activists: using stop and search data collected by an increasing number of cities and states to galvanize supporters and pressure departments to change policies.

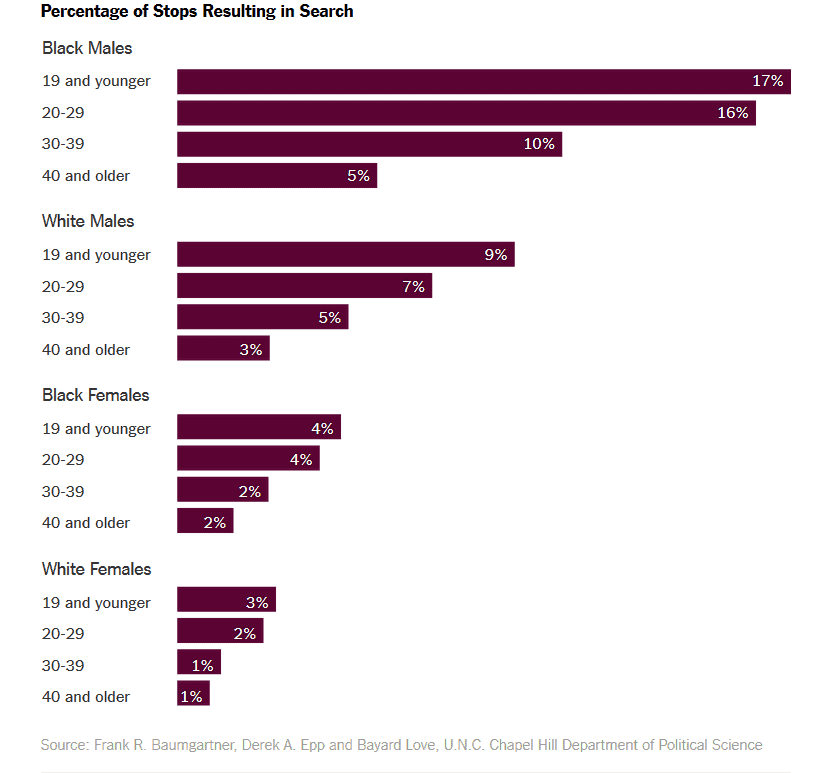

Racial Disparity in Police Searches

An analysis of more than 250,000 traffic stops from 2002 to 2013 in Durham, N.C., shows wide disparities along lines of age, race and gender, with young, black and male drivers more likely to be searched during a traffic stop by the police.

The School of Government at the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill has a new manual for defense lawyers, prosecutors and judges, with a chapter that shows how stop and search data can be used by the defense to raise challenges in cases where race may have played a role.

In one recent case, the public defender representing a Hispanic man on cocaine trafficking charges in Orange County, N.C., got a dismissal after presenting the prosecutor with evidence that Hispanics — while only 8 percent of the local population — had received more than half of the hundreds of warnings issued by the sheriff’s deputy who had made the arrest. The deputy had testified that he stopped the man’s truck for a minor traffic infraction. The prosecutor said multiple factors led to the dismissal.

Defense lawyers’ raising the issue “is gathering steam,” said Alyson Grine, a lecturer at U.N.C. who trains defenders and is an author of the new manual. Several North Carolina police chiefs, she added, have even begun to use the data to sit down with individual officers and examine their search patterns as part of routine management.

Traffic stop data is so powerful a tool for analyzing police behavior that many police departments have begun participating in such studies. More than 50 departments have expressed a desire to take part in a database of traffic stop and search data by the Center for Policing Equity.

Phillip Atiba Goff, a professor at the University of California, Los Angeles, and visiting scholar at Harvard who is compiling the database, said he hoped that by standardizing how the data is collected, police departments that serve economically and demographically similar communities could compare their patterns of behavior to national trends.

The U.N.C. political science professor who processed and analyzed much of the data used by activists in Durham, Frank R. Baumgartner, was careful to make it clear that the figures by themselves were not proof of profiling or intent, though the disparities in searches were so large they called out for investigation. In the spring, the city’s own human relations commission found “the existence of racial bias and profiling present in the Durham Police Department practices.” Other national experts say traffic stop numbers alone do not account for departments that understandably spend more time in high-crime areas, or for commuter demographics significantly different from the composition of neighborhoods.

Durham, home to Duke University, has a rich history of civil rights and social movements, a legacy reflected in the well-organized coalition that pushed for changes. Activists agreed not to call for the resignations of any police or city officials, who could be replaced with more politically savvy executives who might still resist changes. They pressed instead for systemic changes no matter who was in charge. Written consent to search, they said, would reduce disparities and end coercive tactics that the police used to search even in the absence of true, willing consent.

“We were shaming them, and saying, ‘We’re tired of you all talking about how progressive Durham is,’ ” said Ian A. Mance, a lawyer for the Durham-based Southern Coalition for Social Justice, part of the broader group that pushed to reduce the imbalance in searches.

In city hearings and at news conferences, the activists paired abuse allegations with the search data.

“We started with the anecdotes, and then added the scholarship,” said the Rev. Mark-Anthony Middleton, pastor of Abundant Hope Christian Church and one of the leaders of a prominent community group, the Durham Congregations, Associations & Neighborhoods. “We didn’t allow the conversation to devolve into one person’s job.”

Pastor Middleton said community groups remained prepared to work with the chief of police, Jose L. Lopez Sr. “But he has to understand who runs the city,” he added. “He sure does now.”

Chief Lopez remains frustrated at the data’s effects. He believes it was widely misinterpreted to demonstrate something far worse than the numbers showed. City leaders had instructed the police over the last decade to focus more attention on high-crime areas, which in many cases were predominantly black. So of course, police supporters said, blacks were subjected to stops at a higher rate.

“Think about this,” Chief Lopez said. “You have a Puerto Rican police chief in the City of Durham, and you are going to accuse him of racism?”

What is clear, he says, is that departments will have to learn to crunch numbers in order to deflect charges of bias as community groups use their own data presentations to press leaders to curtail police tactics, just as in Durham.

“The pendulum has swung from ‘We trust the police’ to ‘We don’t trust what you say, and you better prove it to us,’ ” Chief Lopez said. “Every police department right now is either putting together data or looking for ways to enhance it, or looking for funding, in order to get on the metric bandwagon as a way of being able to explain what they do and why they do it, and also to prove they’re not doing what they are accused of doing.”

This press clipping originally appeared in the New York Times on November 20, 2014.